- PAGE MENU

- This Old Golden Land

This Old Golden Land

We were delighted to be invited to contribute to the Scottish Pagan Federation's on-line conference held 13-17 May 2020.

Helen's talk on 'Orkney's light' was presented on 14th May 2020.

Here is the YouTube link and below is the transcript of the talk with maps and photographs.

Download Transcript

Download transcript of talk in PDF format.

Transcript

The title of this talk, and the alternative guidebook to Orkney which Mark and I are about to self-publish, is inspired by Phil Rickman, one of my favourite authors. In Rickman’s ‘The Chalice’, his hero has previously made his name as an author, as well as a small fortune, by writing a unified theory of British folklore, entitled ‘The Old Golden Land’. Rickman never tells us much about the contents of the book, only that it is a ‘cult’ book, full of archetypal references, and that his fictional author has struggled ever since to write a sequel – despite encouragement by his publishers.

I so wish such a book existed! For most of my life I have stumbled across hints of an underlying truth that periodically peeks out and says: ‘there are secrets, there is more than this mundane world of offices and motorways’. When I first heard the name ‘Albion’ in my late teens, something reverberated within my heart, likewise with the myths of King Arthur and Robin Hood, but no matter how much I chase this idea, the trail always seems to go cold on me. Yet still I persist in trying to reveal some of the underlying universal concepts running through the collective mythology of this land of Britain.

Globally there’s an almost universal belief that ‘heaven’ and earth were once much closer, that some places are subsequently particularly ‘thin’, and that there was a ‘golden’ age of paradise in the past. This belief manifests in British myth too. One of the more persistent themes in British mythology is a sense of a deep feeling and reverence for the land. There is a pervading concept that the land itself cannot be owned but rather that there is some sort of covenant in operation whereby the land will provide as long as its inhabitants are respectful. The idea that the land itself is a sentient and sacred entity is a constant; those who live upon it must become almost possessed by it: to serve and to be served.

In many ways, Orkney is the golden land. There’s a strange light here. We’re at 59 degrees north, so the sun is never directly overhead, not even at midday in midsummer; we nearly always have the sun at an angle and that gives us the oddest light. This light is desired by artists and photographers – they flock here; indeed, there’s a very prolific artistic community in Orkney, nearly everyone has some sort of creative outlet. When I’m guiding, I always tell my guests that it’s impossible to take a bad photograph in Orkney – I’m not fully joking, the natural light here is kind.

There are times when the light is such that its source doesn’t seem to be fully from the sun. The light seems to be thicker, almost liquid in quality; it drapes itself over standing stones and wildflowers like a wash of honey. Sometimes it’s the stones and the wildflowers themselves which appear to emit the light, not just reflect it from the sun – the whole landscape appears lit up, it glows and pulses light, everything becomes transfused and transformed – it’s like stepping into another world. And that world is a magical Otherworld, one where you don’t need to eat or drink, but just to breathe, where all your illnesses are healed, and all your worries just drift away, and you are utterly lost in the moment.

The truly special times are those which photographers refer to as ‘golden hour’, the hour before sunset, or after sunrise. During these hours, the angle of the sun is such that the light is extremely different. It’s like stepping into the land of faery.

The light in Orkney is ever-changing too. I like to pause, when I have the time, to perhaps watch the same stone for a few minutes as the light shifts and oscillates over its surface; to appreciate the impermanence. Observing the shadows of clouds as they skid and wobble across the hills is another favourite mediation of mine.

This magical, golden, ethereal place was the Orkney that I fell in love with over twenty years ago when I first came here on holiday. There was something that resonated with my soul here and it continued to tug at me long after I left physically, returning to my then home and work in Hampshire. The scenery in Orkney was sublime and the low golden sun was full of every fertile promise as it wrapped the land in a sheen of plenty. The sense that this was in some way ‘the right place for me to be’ was mesmerizingly strong. Orkney was different; it offered sanctuary and safety, a little piece of heaven on earth, my own paradise. Even today, whenever I travel back north to Orkney, driving for hours along the interminable A9, passing through mile after mile of often monotonous scenery, the contrast with Orkney’s gentleness never fails to amaze me. It is as if, beyond the bleak and rawness of much of Caithness and Sutherland, and after an often gut-wrenching ferry crossing, there awaits a land of fertility and abundant plenty, the Summerlands, a Shangri La, as if I have slipped through some sort of temporal and geographical veil. I cannot help but wonder how much that contrast might likewise have impacted on those who travelled to Orkney in the past.

I have since learnt that this siren call from these islands has not only affected me. Other ‘incomers’ have described how, once hooked, they simply could not stay away. One of my closest friends described to me how, when she first moved to Orkney, she would lie in bed at night and feel as if something was physically tugging at her heart to stay. Orkney is the sort of place about which it is possible to become quite obsessive as it beguiles with promises to satisfy your every need. Like Glastonbury and Lourdes and the Boyne Valley it exerts a gravitational pull on certain souls, leaving them unable to function in the ‘real’ world any longer.

Orkney is a long way north: 59 degrees north, the same latitude as the southern tip of Greenland and only about 800 km south of the Arctic Circle. This latitude produces an interesting astronomical phenomenon which ideally needs to be experienced over a full solar year, or even several, to fully appreciate it.

To explain this phenomenon I will need to compare direct experience with scientific knowledge.

I am fully aware on a logical and scientific level that the earth is globe-shaped and it goes around the sun in an orbit, and likewise the moon goes around the earth in its orbit. I am similarly aware that the sun is a star at the centre of a solar system, and that the earth is just one of many planets and other bodies which orbit the sun as satellites. But this is not how I experience the skies. My experience is not of being on a round planet, but of being on a flat earth. The earth does not move, but rather everything goes around the earth. Likewise, when it is night and I can no longer see the sun, it is seemingly not because our planet has spun on its axis and turned away from the sun, but rather because the sun is now travelling under the earth.

My experience of the skies is as a gigantic dome, stretching way above, across which the various astronomical bodies dance and glide in an orderly procession. That is my experience and, despite all the best scientific knowledge that my education has thrown at me, something inside cannot quite get rid of the magical sense that my experience is as valuable as my knowledge, even when they disagree.

And that experience of the skies as a gigantic dome is magnified in Orkney; apart from in Kirkwall and Stromness there is very little infrastructure, no high-rise buildings, no concrete jungles, plus there are few tall trees, and little air pollution. Our views are largely unhindered, we can see long distances and consequently we have big skies. If you live, as most of the world’s population does, in an urban or suburban environment, this will be one of the things that you first notice about Orkney: big skies, which bring with them an expansive sense of space. The experience can be quite humbling.

Orkney is so far north that the length of daylight in winter is only a third of the length of daylight in summer. At the equinoxes, the sun rises in the east and sets in the west (this is true of the whole world), and the length of day is twelve hours and the length of night also twelve hours. The nearer you travel to the equator, the less variation there is between the length of day and night throughout the year. But in Orkney, at the midsummer solstice, the sun rises in the north-east, spends the best part of nineteen hours travelling in a massive circuit across the skies, to finally set in the far north-west. Whereas, at the midwinter solstice the sun rises in the south-east, trips along the horizon – depending on where you view it from, it only just seems to skim the tops of hills – and then, after six brief hours, sets in the south-west. At 59 degrees north, Orkney is at precisely the latitude where, if you plot the positions on the horizon where the sun rises and sets at the winter and summer solstices, these four points, when joined together, will form a square. This only happens at this latitude (and presumably also at 59 degrees south, which will be somewhere near the Antarctic).

This means that the annual solar cycle in Orkney has an almost stretched feel to it. When I lived a thousand miles south of Orkney, in southern Hampshire, the winter days were not so noticeably short and the summer days were not so noticeable long; yes, there was a difference, but not in such an exaggerated manner.

The change between the position of the sunrises (and the sunsets) in the middle of summer and the middle of winter is 90 degrees, a quarter of the sky, a right-angle. Because the sun changes where it rises and sets through the year so dramatically in Orkney, it is possible to work out the time of the year from the position of the sunrises and sunsets in the landscape.

But the sun doesn’t change its position in the landscape in a steady manner, rather it makes its most dramatic changes in position around the time of the equinoxes. Twice a year, within a four week period, for two weeks either side of both equinoxes, the length of the day changes by about two hours (that’s a difference of about 4 minutes additional – or less – daylight every day), whereas for a similar period of time either side of both solstices, the length of the day only changes by about quarter of an hour (that’s a difference of only about 30 seconds more or less daylight each day). In other words, the changes in day length speed up around the equinoxes and slow down around the solstices.

Likewise, the position of the sun’s rising and setting in the landscape changes most around the equinoxes and least around the solstices. At the solstices, the sun appears to rise and set in the same place in the landscape for about three days in a row. And that’s what solstice means: ‘sun stands still’. Although the science insists that it is not the sun that moves but rather the earth, our experience suggests that it is the sun and all the other astronomical bodies which move and that it is the earth which is static as the fixed and central point.

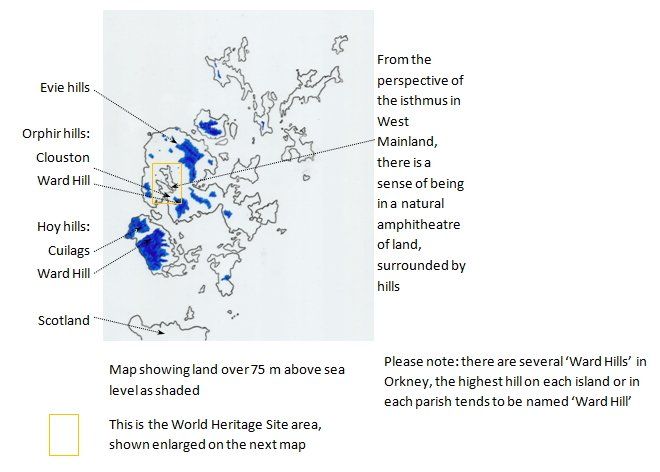

The largest of the islands of the Orkney archipelago is named, in typical Orkneycentricity: ‘the Mainland’. West Mainland is a gigantic natural amphitheatre of land, ringed by hills, with two enormous lochs in the middle. Between the two lochs lies a thin isthmus of land, which runs directly south-east to north-west – this isthmus is naturally aligned on the sunrise in midwinter and sunset in midsummer. Viewed from this cauldroned area, to the south-west, are the two largest hills in Orkney: the hills of Hoy. It is behind these two hills that the sun appears to set in midwinter. It is almost as if the landscape and the solar alignments are in some sense geographically synchronised.

This geography is the fortuitous combination of a set of natural phenomena with which Orkney is blessed. Fortuitous because this bowled area of land in West Mainland is, in many ways, a natural temple to the sun. Fortuitous too because the precise combination of lack of wood with which to build, plus convenient sandstone which makes a perfect alternative building material, means the archaeology is more durable. And fortuitous because the lack of developed infrastructure and non-intensive agriculture means that the archaeology has survived. This is why there is a popular saying in Orkney that you only need to scratch the surface of the land and it bleeds archaeology: ploughing often brings a scattering of underground archaeology to the surface.

In the summer, for about ten weeks, four or five weeks either side of the solstice, it does not get dark enough to see the stars. Instead there is just a short period of twilight inky-blue nearly-darkness, which is locally called the ‘simmer dim’. It is light enough to read by at midnight, if you don’t mind eye strain. You cannot set your body-clock by the sun in Orkney, if you do, you will hardly sleep in summer, and you will sleep constantly through winter.

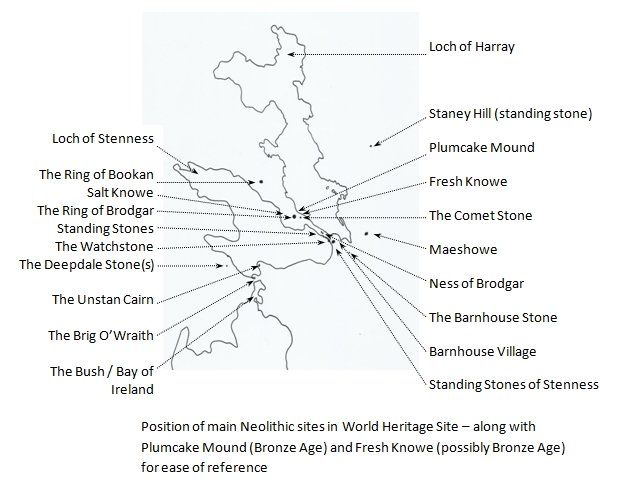

The focus of any Orkney tour, any visit, for anyone interested in archaeology, tends to be on the Neolithic stone circles of West Mainland. The World Heritage Site ‘The Heart of Neolithic Orkney’ is what Orkney is probably most famous for. But it is the standing stones that are protected by World Heritage Site status, not the landscape, or at least not much of it. However, if you were to take the stones out of the landscape, or change the landscape sufficiently, an essential part of the archaeology will inevitably be lost. Today we are almost encouraged to think that the landscape is sacred because of these monuments but that way of thinking is incomplete: this landscape is sacred in its own right. Its sacredness is enhanced by the addition of these stones, which in turn become increasingly sacred themselves by their positioning here. It is a cyclic act of co-creation.

In Orkney, the natural landscape hasn’t changed that much since the Neolithic sites were built. Certainly the coast lines have changed and the water levels have risen but, except in Kirkwall and Stromness, there is no high-rise urban infrastructure to obscure views, nor are there any massive transport projects which have bored through hills or levelled valleys. The topography of both the near and far horizons is broadly similar to what would have been visible thousands of years ago. For archaeologists, this is a fortunate situation compared to other ritual landscapes of the Neolithic such as Stonehenge, Avebury, and the Boyne Valley.

In West Mainland, the modern features which most distract us from seeing the landscape as it was are probably the roads. The houses and pylons are so obvious, we know to ignore them, but the roads hypnotise us into thinking that they are the main, possibly the only, way through the terrain. They are not, they never were – but they have the power to close down our perception of the landscape as permeable; they constrain its traversal to thin corridors, limiting our sense of potential freedom of movement through space.

So whenever possible, I try to ignore the roads and, if safe to do so, walk. I would encourage any visitor to walk too – there is an accessible network of footpaths which facilitate doing so, a good place to start is from the Standing Stones of Stenness – because when you choose to walk, you take yourself down into a prehistoric pace. The first thing you will probably notice is that this area of West Mainland is like a natural cauldron; there is a ring of hills all around so that, from within, it is like being held in the cupped palm of a huge hand. There is a feeling of protection from the elements here. Then, within, as if puddling in the bottom of a gigantic bowl, there are two massive lochs with a thin strip of land running between them. In Orkney, to the best of our current knowledge, stone circles only occur along this isthmus (or at least within its visual vicinity): this area is like an island within an island.

In the Mesolithic it is likely that this isthmus was wider than today and that these two lochs had not fully formed; they may have just been marshy land and may not have become lochs until the early Neolithic – the sea broke through at the Brig O’Waithe about 3700 BCE and the sea levels continued to change and did not stabilise until about 2000 BCE – but even so the isthmus of land would have risen as a ridge of higher land in the middle of this natural amphitheatre. It would have been an ideal place to trap prey for Mesolithic hunters; deer for example could have been funnelled into the Ness of Brodgar area, as it became narrower and narrower the prey would have been trapped, their only escape being to swim or stumble across the marshy swamp. It would certainly have been a direct and possibly more convenient route for anyone traversing the landscape, just as it is today. We know from evidence elsewhere that Mesolithic people chose to walk along natural ridge-ways, eventually creating a network of paths and clearings throughout the British Isles. It is likely that this area, now known as the Ness of Brodgar, was an important place for the Mesolithic people of Orkney. This piece of land may have held memories of ancestral hunting ambushes into the Neolithic and beyond.

From this area, the most distinctive visual features are the hills of Hoy, which lie to the south-west, on the southern island of Hoy. Seen from this area of West Mainland, there are two large hills: the Cuilags on the right (at 433 m above sea level) and Ward Hill on the left (at 479 m – the highest point of all Orkney). There are other hills which are occasionally visible beyond and between these two: Moar Fea (304 ms) and some lesser slopes of Ward Hill.

The hills of Hoy are associated with an important astronomical event: for a period of about eight weeks, either side of the midwinter solstice, from particular places in West Mainland, the sun appears to set between and behind these two hills. In the very depths of winter, when Orkney days are as short as six hours, from certain directions the sun appears to set behind Ward Hill and then reappears, flashing in the gap between Ward Hill and the Cuilags, before setting again; the sun effectively setting twice.

The hills of Hoy were obviously important to the Neolithic people who built some of their more impressive monuments in this area but, given they so dominate the landscape where the World Heritage Sites are concentrated, it is possible that these hills were of visual importance from other sites too.

Obviously, the profile of the hills of Hoy changes depending on where in the landscape they are viewed from. I believe that one of the reasons why the main Neolithic monuments were built where they were built was in order to provide optimised vistas of the hills of Hoy. I further believe that this sequence of optimised, but changing, vistas preserves part of an original pre-Neolithic landscape mythology. By walking between these sites, and observing how the profile of the hills of Hoy changes, it may be possible to catch glimpses of this myth.

I was inspired to think in this way when I heard ‘Before there was, there was not’ spoken in my head, unbidden but quite clear, as I walked around the Standing Stones of Stenness. These are the starkly beautiful opening words from the Norse ‘scriptures’, the Elder Edda. Like many spiritual pilgrims before and after me, I was there trying to unravel the mysteries through experience ... and, when I heard those words, I realised that to understand these sites, I had to first consider what was here before they were constructed: when there was simply ‘not’.

So, starting to the south, from Maeshowe, I shall describe how the profile of the hills of Hoy changes as one moves through the landscape. At first, from Maeshowe, only the tops of the two hills of Hoy are visible. Any hills in between are not visible, being completely hidden behind the near horizon formed by the hill at Clouston (HY 300 110) to the south-west.

Travelling north-west towards the Standing Stones of Stenness, the most southerly point of the outer henge here is exactly where the middle hill, between the hills of Hoy, first becomes visible and the hill at Clouston no longer completely disrupts the view of it:

From the centre of the Standing Stones of Stenness, the hills of Hoy form an interesting shape, with Moar Fea being symmetrically arranged between Ward Hill and the Cuilags, but still not fully visible. Many people comment that the profile of the hills from the centre of this site looks like a pregnant woman lying on her back with her legs open, displaying her fecund belly:

Further north-west, from the Watchstone, Moar Fea remains symmetrically arranged between Ward Hill and the Cuilags, and gradually becomes more visible as one continues walking north. It is as if the landscape goddess is becoming more heavily pregnant.

Just north of the Watchstone you have to walk along a short bridge under which the waters of the lochs of Harray and Stenness meet – no one knows whether this bridge would have been present in prehistory but this is almost certainly the route which people took because otherwise it is an incredibly long way around either loch. Perhaps there was a timber trackway here, like Somerset’s Sweet Track, perhaps stepping stones, or perhaps there was a ferryman to row people over the waters.

Following the paths northwards towards the Ring of Brodgar, the Comet Stone is sited at the point in the landscape where visibility with the hills of Hoy is lost. Visibility is restricted by the ridge immediately to the west, which forms a near-horizon and is studded with tumuli. Visibility with the hills of Hoy is only regained fairly near to the southern entrance of the henge.

The hills of Hoy are not visible from every part of the Ring of Brodgar, but only from the south-western side where the profile is of two smaller hills between Ward Hill and the Cuilags. These small hills are Moar Fea on the right and a part of the Cuilags on the left. Where the smaller hills meet, there is a notch between them which is reminiscent of a feminine vulvic notch. Some people comment that the profiles of both of the smaller hills look like babies’ faces. The four hills are quite symmetrical from this part of the landscape:

Travel even further north, climbing the near horizon to Bookan, where the rough lumps and bumps of the Ring of Bookan are visible, the least known of the (possible) henge sites. From Bookan, the twin hills of Hoy no longer frame Moar Fea, instead another hill nestles between them, this hill being part of the lower slopes behind Ward Hill. The profile of the hills are now similar to that as viewed from the Standing Stones of Stenness, only the central hill is different, even though it looks the same; if there is a landscape myth associated with these hills and this particular route through the landscape, then it is likely to be a cyclical myth, possibly a solar one:

In summary, the smaller hills which appear between the hills of Hoy change in their visibility depending on where in the ritual landscape they are viewed from. The overall effect is of a single rounded central hill becoming increasing visible, splitting into a view of two hills, and reverting to a single rounded central hill. The hills of Hoy, the smaller hills between them, and the sequence of what becomes visible, has a cyclical symmetry to it. There are hints here of archetypal myths: perhaps of landscape goddesses and cosmic pregnancies. Landscape goddesses are known elsewhere, there are several in Scotland, the most famous being Lewis’ Cailleach na Mointeach – the ‘Sleeping Beauty range’ – where the silhouettes of the hills form the shape of a supine woman. In the British Isles it is fairly common for double hills to be synonymous with breasts and clefts in hills with vulva.

Given that the sun will appear to set between these hills in midwinter, was there some sort of myth connecting the (re-)birth of a solar deity / child with this part of the landscape? Or does the symmetry of the hills of Hoy, as seen from the Brodgar viewshed, hint that the myth contains the archetypal story of rival brothers? Perhaps there was an annual myth-cycle with set rituals being re-enacted, or stories related, at certain times of the year and at each of the different sites. Frustratingly, it is impossible to deduce any more without dwindling to guesswork, these are elusive hints and no more; it is like grasping at smoke skeins.

I have found the recognition of the natural topography of the landscape to be a vital initial stage in starting to understand and appreciate the Mesolithic landscape, and the later Neolithic sites within it, and how they all interact to form a visually inter-connected ritual landscape akin to a giant spider’s web (albeit perhaps one without a single focal point at the ‘centre’). The people who inhabited this landscape made careful calculations in order to create precise viewpoints and alignments between individual sites, monuments, the landscape as a whole, and the skies above. I believe that the stones and the landscape co-create and endorse each other in a continuous and cyclical process; their sacredness lies in this unique combination of natural and built environments.

I have come to appreciate that the Neolithic ritual landscape of West Mainland has much to do with the sun’s apparent interaction with the land. At certain times of the years, and from specific viewpoints in the landscape, the sun appears to rise from, and enter via, specific clefts and features on the horizon. These are insights which could only have come gradually, from exposure to the landscape over many years of watching and noting.

The light in Orkney is constantly shifting and, as it does, it reveals fresh ways of looking, new ways of seeing, subtleties that had been missed before. In the same manner that the archaeologists have learnt to recognise the immense quantity of art at the Ness of Brodgar, some of it only visible when the sun is at a certain angle, so too the light has taught me to look more than once. It is necessary to look and to look again and to keep on looking in order to allow the light to be fully revelatory.